Image copyrightNASA/NOAA

Image copyrightNASA/NOAAThe past year has been a busy one for hurricanes.

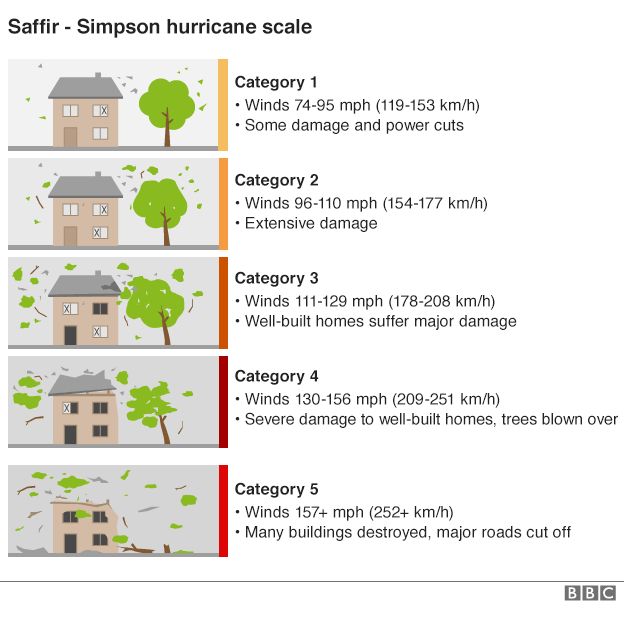

There were 17 named storms in 2017, 10 hurricanes and six major hurricanes (category 3 or higher) – an above average year in each respect.

The 10 hurricanes formed consecutively, without weaker tropical storms interrupting the sequence.

The only other time this has been recorded was in 1893.

Are these storms getting worse? And does climate change have anything to do with it?

A year of records

This Atlantic hurricane season has been particularly bad.

There was Harvey, which pummelled the United States in August.

It brought the largest amount of rain on record from any tropical system – 1,539mm.

It caused the sort of flooding you’d expect to see once every 500 years, causing $200bn of damage to Houston, Texas.

Ironically, this was the third such “one every 500 years” flood Houston had suffered in three years.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESSeptember brought Irma, which devastated Caribbean communities. It was the joint second strongest Atlantic hurricane ever, with sustained winds of 185mph.

Those winds were sustained for 37 hours – longer than any tropical system on record, anywhere in the world.

Next came Hurricane Maria – another category 5 hurricane, with sustained winds of 175mph – which destroyed Puerto Rico’s power grid.

Finally, Hurricane Ophelia span past Portugal and Spain – the farthest east any major Atlantic hurricane has ever gone.

Despite this, 2017 wasn’t the worst year in some key respects.

It didn’t produce the strongest storm – that was Hurricane Allen in 1980, with sustained winds of 190mph.

Nor did it have the greatest number of storms – that was 2005, which saw an incredible 28 named storms, including seven major hurricanes. One of them was the infamous Hurricane Katrina.

But 2017 was probably the costliest. Estimates for the cost of the hurricane season vary and continue to be revised, ranging up to $385bn.

By comparison, 2005 racked up $144bn in damage according to the National Hurricane Center – about $180bn today, adjusted for inflation.

It has certainly been a bad year. But over time, are hurricanes getting worse?

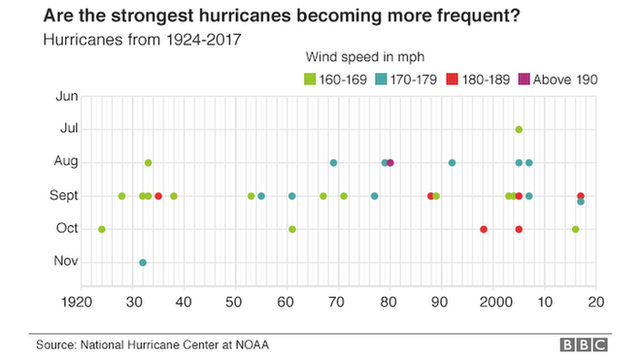

There have been 33 of the strongest category 5 hurricanes since 1924. Eleven of these have occurred in the past 14 years.

We know that hurricanes are powered by warm seas and over the past 100 years global average sea temperatures have risen by about 1C.

But when you look at the total strength of storms in each year since records began, some years are more fearsome than others.

Meteorologists use something called accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) to calculate the total wind power of all the storms in any given year.

As you can see from the following chart, there’s no clear upward trend.

Why not?

Even though seas are getting warmer, other factors can prevent hurricanes forming in particular years.

Saharan dust can interfere with hurricane formation as can the close proximity of African storms to the equator.

But one of the great weather ironies is that hurricanes hate strong winds.

Strong winds in the Atlantic interfere with the circulation of air through a developing storm. This stops the storm growing into a hurricane.

During a phenomenon called El Niño, the Pacific Ocean near the equator gets warmer than usual. This affects global wind patterns, leading to stronger winds in the Atlantic.

That means El Niño years tend to be quiet years for hurricanes.

But when the Pacific is cooler (known as La Niña), the reverse is true – making it easier for hurricanes to form. And 2017 is a La Niña year.

In fact, the total storm strength in La Niña years has been rising decade by decade.

Land drainage

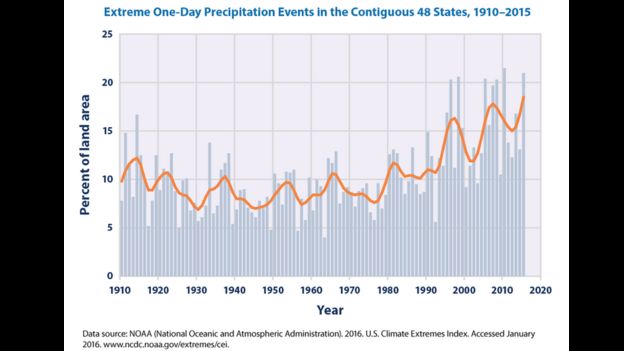

High winds are just part of the story. Climate change affects hurricane seasons in other ways, too.

Rainfall during hurricanes can be devastating. Hurricane Harvey would have brought severe flooding to Houston regardless of climate change.

But it is reasonable to assume that Harvey brought more rain than it would have done 100 years ago.

Global air temperatures have also increased by about 1C in the past 100 years, and warmer air holds more water.

That’s likely to be behind the increasing frequency of extreme rainfall events seen in the US in recent decades.

Image copyrightEPA

Image copyrightEPABut the location of housing compounded the damage.

Houston’s population has more than doubled since 1960 to more than two million people. Housing developments are expanding into more marginal, poorly drained land.

This puts more people in harm’s way.

Climate change is also causing seas to rise.

Melting glaciers and land-based ice sheets contribute to higher sea levels.

Also warmer water occupies a larger volume. So as seas warm up, sea levels rise.

In the US, the largest sea-level rise is around the coast of the Gulf of Mexico – about 9.6mm each year at Eugene Island, Louisiana.

All of this is increasing vulnerability to flooding when hurricanes and their associated storm surge reach land.

A warmer world is bringing us a greater number of hurricanes and a greater risk of a hurricane becoming the most powerful category 5.

There’s an increased risk of flood damage – whether related to climate change, rising sea levels or more people moving into flood-prone areas.

Archive of posts from Saba-News.com Archive Saba News

Archive of posts from Saba-News.com Archive Saba News